From domestic violence to public rallies and terrorist acts, it’s clear that anger, aggression and violence are widespread in society.

Although these terms – anger, aggression, violence – are often used interchangeably, they are different and must be uniquely managed by care professionals and policy makers.

Cases of mass murder, domestic violence, and links between violent video games and aggressive behaviour highlight the importance of these differences.

Emotion vs behaviour

Anger is an emotion that motivates and energises us to act.

Anger can drive destructive behaviour, such as in the Charlottesville riots, where public protesting turned violent. But anger can also energise people to make constructive changes.

Many great reformers such as Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi channelled their anger to great social benefit.

Peaceful protests such as the Women’s March and the March for Science have done the same.

Aggression is a behaviour motivated by the intent to cause harm to another person who wishes to avoid that harm.

Violence is an extreme subtype of aggression, a physical behaviour with the intent to kill or permanently injure another person. Aggression and violence are rarely constructive, and are only sometimes motivated by anger.

These differences are highlighted by the Columbine school shooter Eric Harris. Harris was receiving anger management treatment a year before the shooting and, in his essay, noted its efficacy and his own commitment to controlling his anger.

But the next year Harris and his friend Dylan Klebold coldly drew up plans to kill their classmates and destroy their school. Their diaries revealed some anger, but most notable were their thoughts, beliefs, fantasies and attitudes, many of which involved and approved violence. Clearly, anger management did not sufficiently change the way Harris thought about aggression and violence.

A model of aggression

Aggression can be physical (punching), verbal (hurting another with words), and relational (damaging another person’s relationships). Aggression can also differ in three key ways:

- the goal: harm the victim versus benefit the perpetrator

- level of hostile emotion, such as anger

- degree of “thinking-through”.

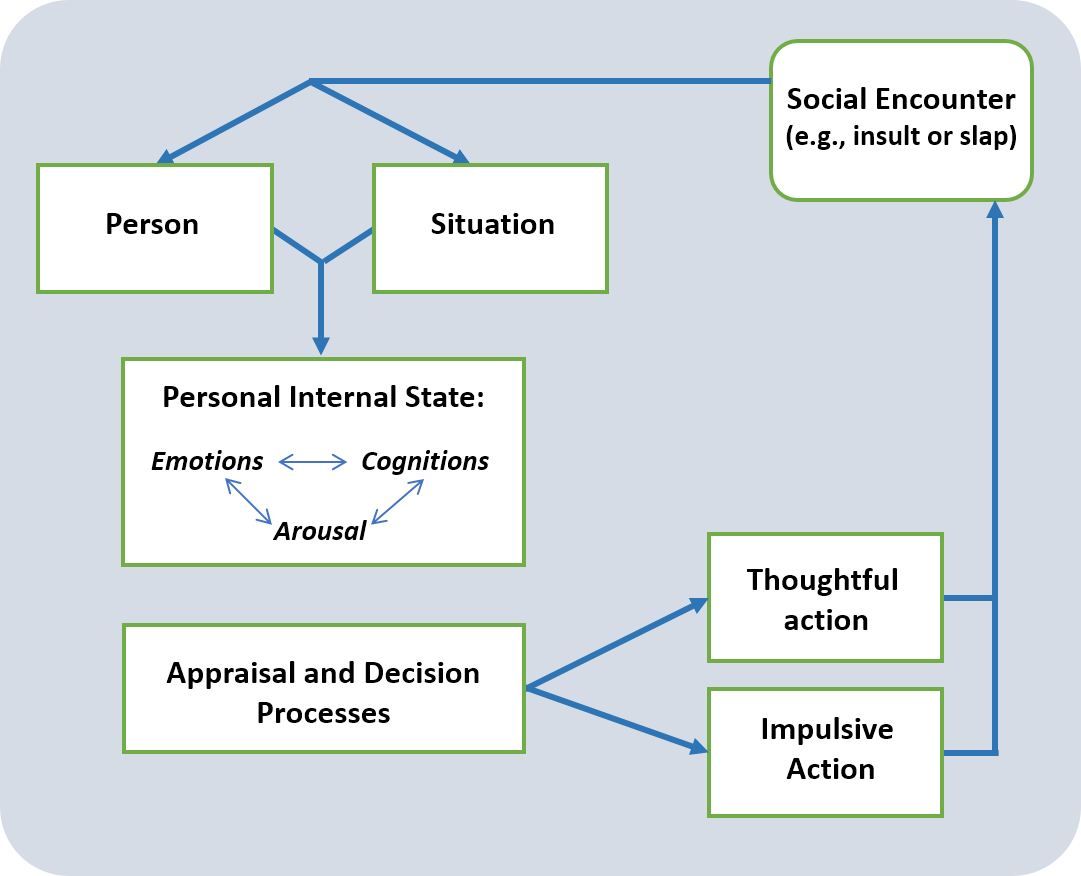

The General Aggression Model (GAM) is the most widely used current model of aggression. The GAM suggests that certain events (an insult, or slap) can activate aggressive thoughts, aggressive emotions or a combination of both, which can trigger an aggressive impulse.

While elevated physiological arousal may increase the likelihood that the person will enact that impulse, thinking through consequences and considering alternate responses usually reduces aggression. Crucially, anger need not be present.

The GAM (adapted from Anderson & Bushman, 2002).

Although anger can be channelled constructively, it seems clear that aggressive behaviour can compound. Aggressive actions most often increase the likelihood of further aggression, and enacted aggression does not reduce aggressive impulses.

Violence and aggression beyond a mild degree almost always involve additional factors. A tendency towards impulsivity and keeping company with delinquent peers are risk factors. Protective factors include positive parenting, and conflict skills.

The GAM and these findings have clear implications for how each factor should be managed. Anger can be channelled but aggression cannot. To reduce the incidence of aggression, or of aggression escalating to violence, risk factors should be reduced and protective factors enhanced.

Reducing arousal and increasing opportunities to “think-through” will reduce the likelihood of both aggression and violence.

Policy and practice

It can be easy for professionals, such as those working in law enforcement; social services; and mental health care, and policy makers to confuse the terms anger, aggression and violence, leading to avoidable errors.

Sometimes, we think that curbing anger is enough to stop aggression. But anger management can be ineffective unless complemented by strategies to change aggressive attitudes and beliefs.

For example, combating domestic violence requires an integrated approach that works with feelings (like anger), challenges aggressive thoughts, identifies and mitigates risk factors, and encourages calmness, reflection and nonviolent solutions.

This is exemplified in the case of Neha Rostagi, who suffered ten years of abuse at the hands of her husband despite him being mandated to 52 weeks of anger management classes for previous domestic violence charges.

Mistaking aggression for violence can also lead to public confusion about violence in media such as video games. Detractors of research showing that violence in games is linked with aggression point out that societal violence has decreased while media violence exposure has increased. They – wrongly, in our opinion – conclude that this indicates media violence does not influence aggression.

Apart from the obvious logical flaw – one risk factor can be increasing while others are decreasing – this confuses aggression and violence. Although some links to violence have been found, the vast majority of research in this area points to increases in lower level aggressive behaviours being linked with exposure to media violence.

Statistics about societal violence, such as murder rates, simply do not apply. Rather, media violence research should be taken into account by policymakers because it has implications for acts of everyday aggression such as bullying, and saying cruel things, or sabotaging other people’s relationships that are seen as important in homes, schools, and professional practice.

Policymakers, professionals and society at large would benefit from clearly differentiating anger, aggression and violence and responding appropriately to each.

We would like to thank Distinguished Professor Craig Anderson and Professor Douglas Gentile, of Iowa State University, for their comments and advice

Source: The Conversation – Chanelle Tarabay and Wayne Warburton

Chanelle Tarabay is a PhD Candidate in Psychology, Macquarie University

Wayne Warburton is a Senior Lecturer , Macquarie University